S3 Graphics: Gone But Not Forgotten

These days it'southward rare to see a new hardware company suspension ground in the world of PCs, but 30 years ago, they were popping up all over the place, similar moles in an arcade game. This was especially true in the graphics sector, with dozens of firms all fighting for a slice of the lucrative and nascent market.

I such company stood out from the crowd and for a brief few years, held the top spot for chip design in graphics acceleration. Their products were so pop that almost every PC sold in the early on 90s sported their technology. But simply ten years after its birth, the firm divide upwardly, sold off numerous assets, and rapidly faded from the limelight.

Bring together the states equally we pay tribute to S3 and run into how its remarkable story unfolded over the years.

The formation of S3 and early successes

The tale begins right at the showtime of 1989, an era of the likes of the Apple tree Macintosh SE/xxx, MS-DOS 4.0, and the Intel 80486DX. Personal computers and so generally had a very express display output, with the drawing handled past the CPU and ordinarily but in single fleck monochrome; but with a suitable add-in card or expansion peripheral, accelerated rendering with 8-fleck color was possible.

Prices for such extras could start at $900 and often go much higher than this, and it would be for this marketplace that Dado Banatao and Ronald Yara would put together a new startup based in Santa Clara, California: meet S3, Inc. Banatao's story is worthy of its own tale, as is Yara'due south, and past this fourth dimension, they were both highly successful technology entrepreneurs and electrical/electronics engineers.

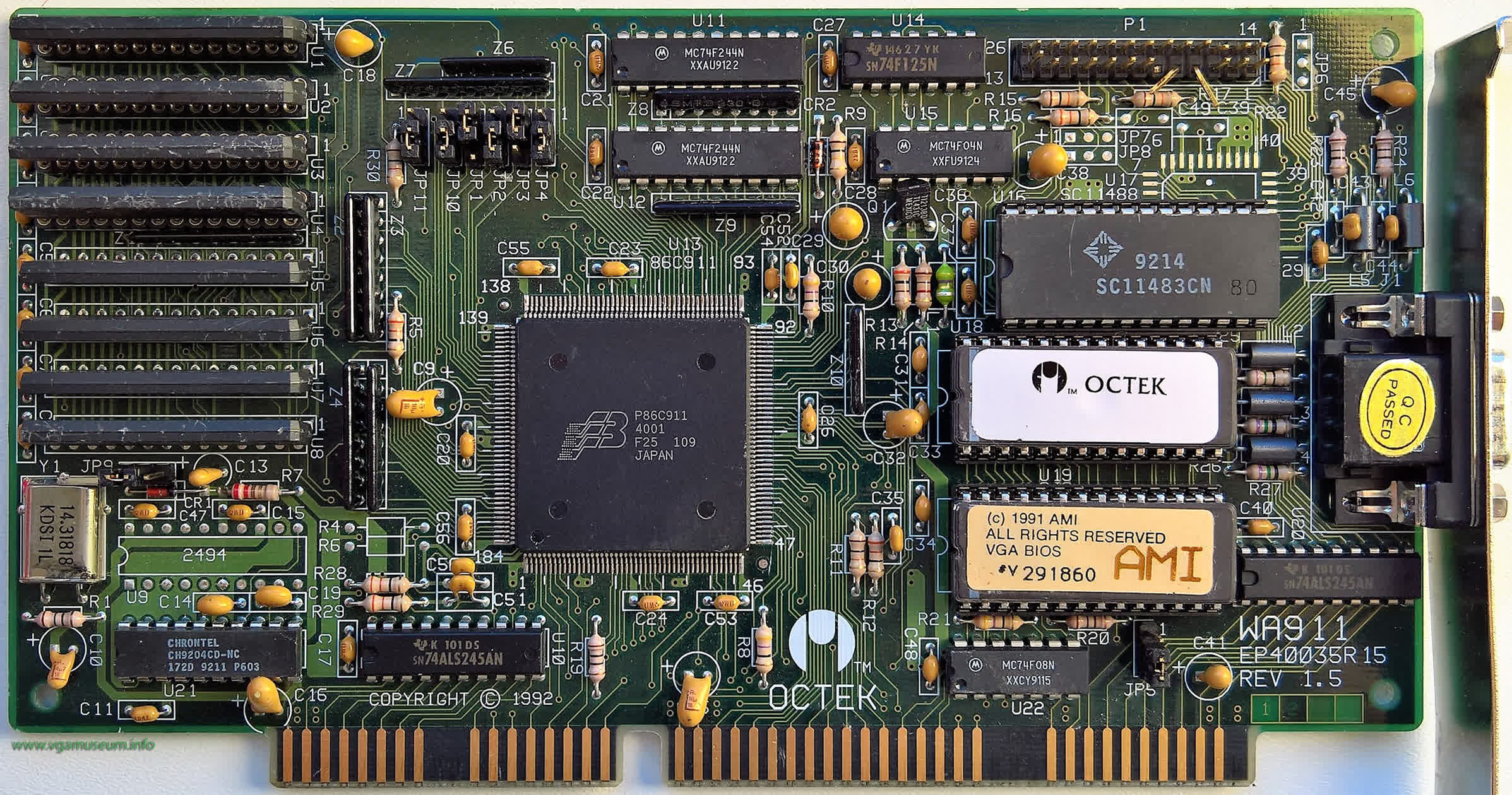

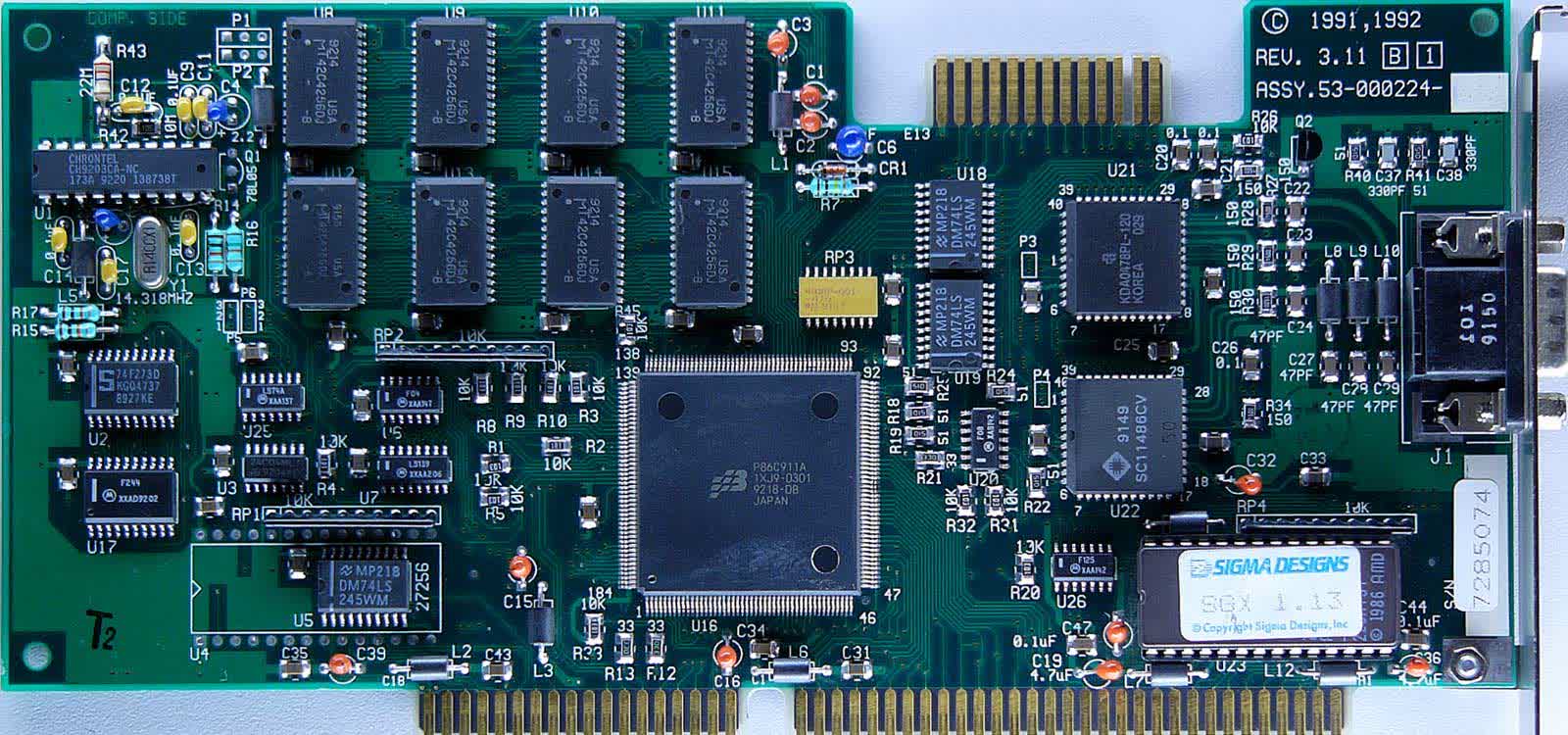

Inside two years, they had their first product for sale: the P86C911 (besides known every bit the S3 Carrera). This scrap accelerated line drawing, rectangle filling, and the raster operations in Windows, mostly involving what are known as bit block transfers. This is where small-scale arrays of data, that every bit a whole make up the entire screen, are moved about, overlayed, copied, etc.

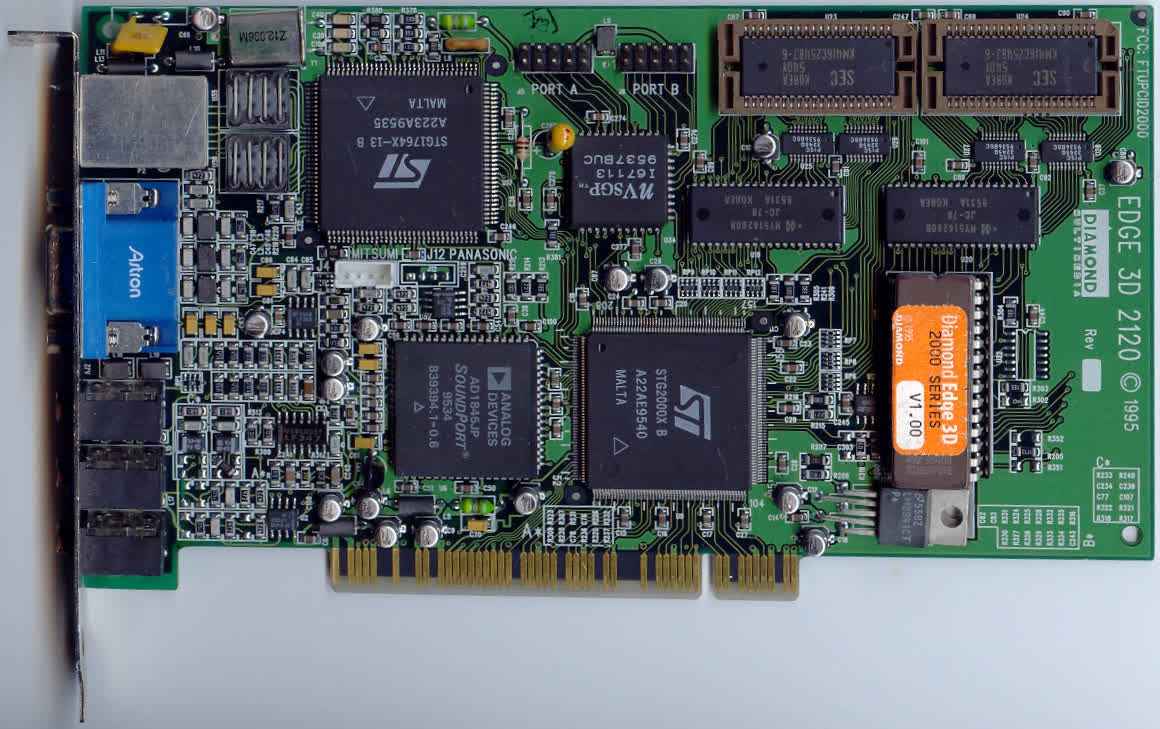

Just equally AMD and Nvidia do today, S3 used other companies to manufacture and distribute the chips, which would then be purchased past add-in lath vendors for their own products. Famous names, such as Diamond Multimedia and Orchid Technology, released cards sporting ane MB of VRAM, an output equally high every bit 1280 x 1024 in 16 colors, and a 16-chip ISA connection organisation.

Reviews were quite favorable at the fourth dimension -- it wasn't the fastest accelerator out in that location, only it was competitively priced. The criterion for all so-called 2D accelerators and so was the Mach series of chips from ATi Technologies, only where an ATI Graphics Ultra card powered by the Mach 64 retailed at $899, cards with the S3 P86C911 could be had for as fiddling as $499.

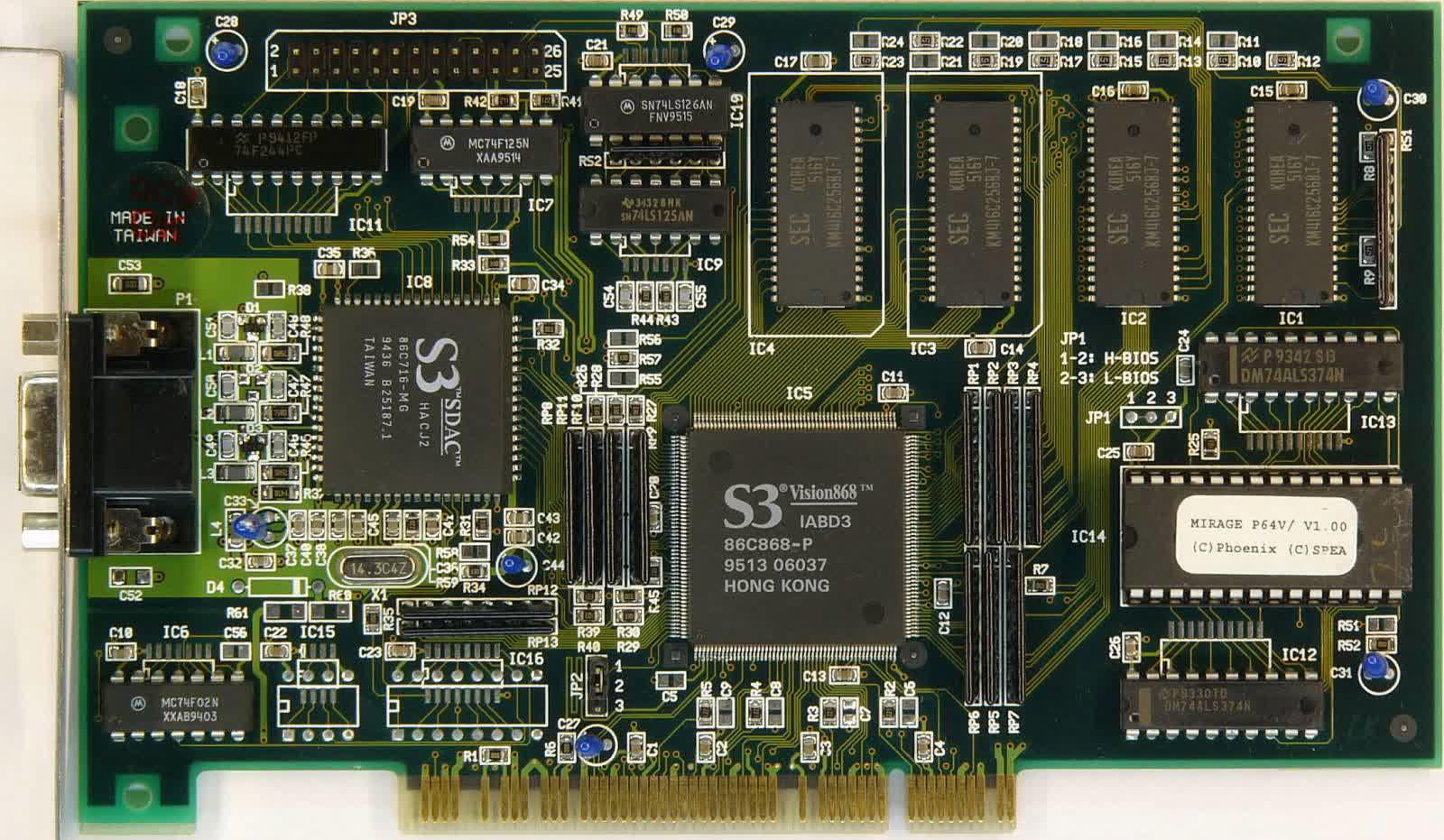

In those early on days, S3 maintained a salubrious development bicycle, and continued to amend and modernize their flake blueprint. By 1994, add-in lath vendors were using the new Vision series of accelerators: full 16-bit color output at 1280 10 1024, and up to 4 MB of fast page mode (FPM) or extended information out (EDO) 64-bit DRAM. There was even acceleration for MPEG video files.

Again, such products weren't the fastest available, but they were significantly cheaper than the contest. Naturally, this caught the heart of organisation builders and other OEMs, and S3 fries would grace many person's outset PC.

A quick glance at the to a higher place image, from High german menu vendor Spea, highlights a detail issue that manufacturers faced in the mid 90s: multiple separate chips were required to handle diverse roles. At the least, one was needed for the main clock and another for the digital-to-analogue conversion (i.due east. the RAMDAC).

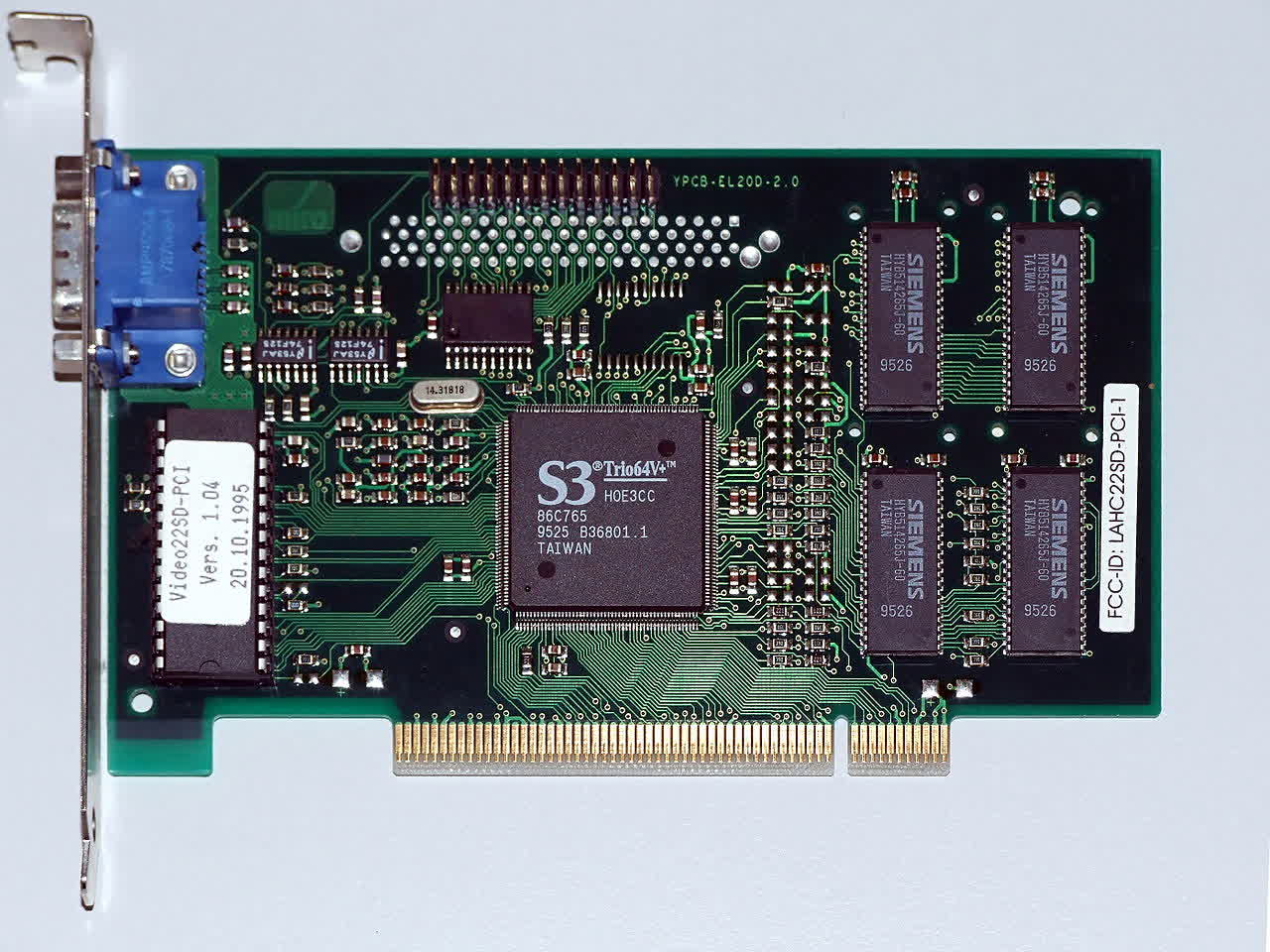

To that end, S3 released the Trio flake series a year later on, which integrated the graphics acceleration circuits, with the RAMDAC and clock generator. The result was a notable reduction in costs for card vendors, which pushed S3's popularity fifty-fifty further, giving them the panthera leo'south share of brandish adapter market place.

Past 1995, game consoles such every bit the Sony PlayStation and Sega Saturn clearly demonstrated the direction that the graphics market was now dedicated towards, and with S3 at the pinnacle of their powers, they were ane of the starting time chip designers to meet these new demands, with an 'all-in-one' offering.

Given how well they had mastered 2D and video dispatch, how hard could 3D be?

Another dimension and the first failures

The best selling PC game in 1995 was Command & Conquer, a existent-time strategy game initially released for DOS that used 2nd isometric graphics. All the same, console owners were beingness treated to 3D images, similar to those being generated in arcade machines.

Then the pressure was on for hardware makers to provide acceleration in this area, too. Software support was already bachelor, as OpenGL past then was 3 years old, and Microsoft had snapped up RenderMorphics at the start of 1995, in order to integrate their Reality Lab API into their forthcoming Windows 95 (to ultimately become Direct3D).

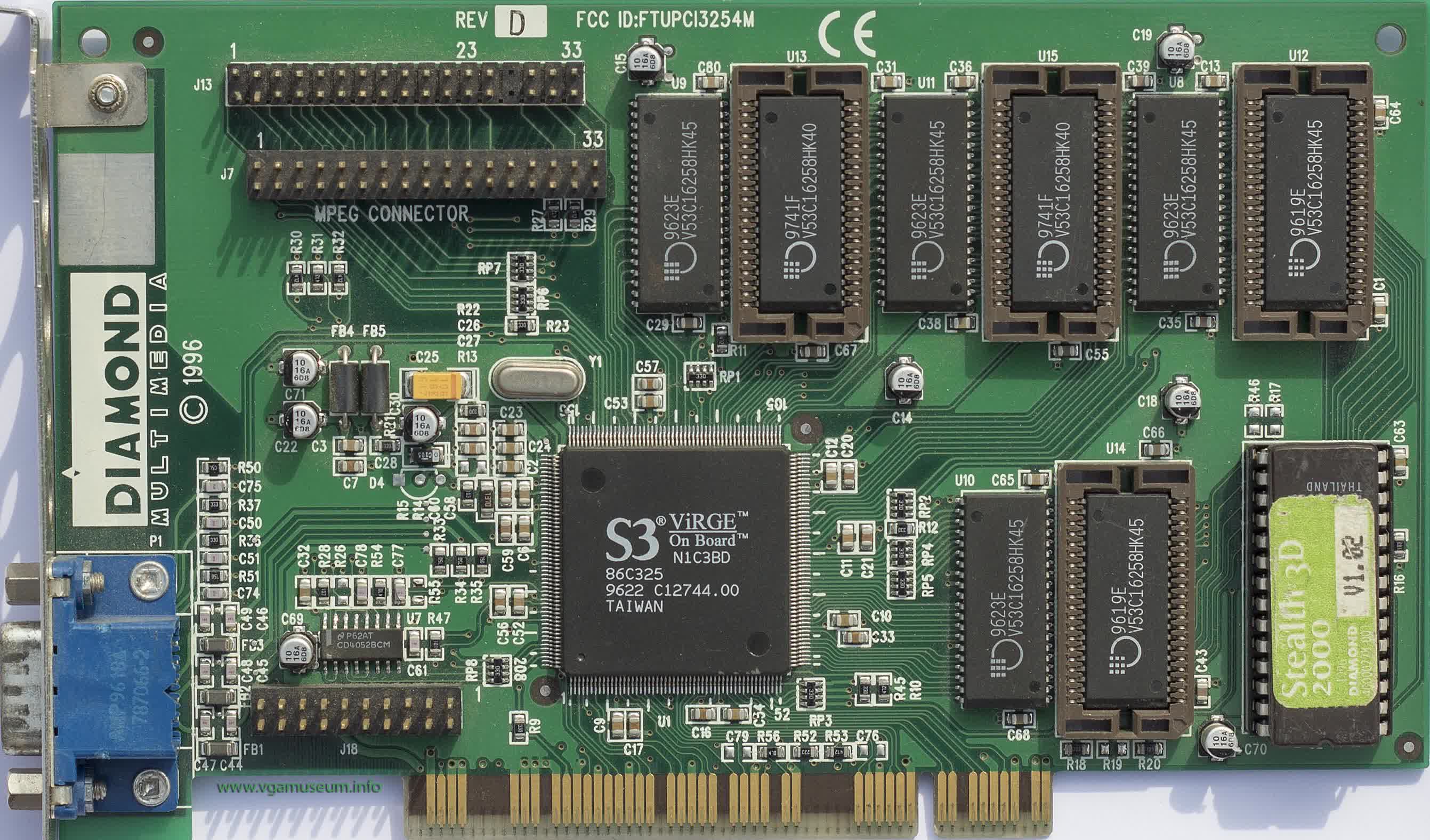

By the end of the yr, S3 launched the ViRGE ('Virtual Reality Graphics Engine') chip; essentially an improved Trio with some 3D capability shoehorned into it (marketed as the S3d Engine).

Add-in cards using the processor weren't readily available until early 1996, and these first offerings were met with universal ambiguity. Up to this signal, 3D games on the PC were nearly e'er rendered via the CPU and when handling bones polygons, lit via Gouraud shading and unfiltered textures practical, the ViRGE was by and large a little faster than the best CPUs of that time.

The "S3 ViRGE" was generally a little faster than the all-time CPUs of that fourth dimension...

However, with whatsoever other boosted 3D characteristic applied (such every bit texture filtering or perspective correction), the performance would nose swoop, especially at resolutions equal to or greater than VGA (640 ten 480). At that place were a number of reasons for this, but two aspects stood out confronting the others.

Firstly, developers had to apply S3's own API to have advantage of the 3D acceleration, equally they didn't offer whatsoever OpenGL support in their drivers initially. Proprietary APIs aren't necessarily worse than open sourced ones, but in one case other manufacturers released their own 3D chips, with total compatibility with OpenGL, few developers bothered to brand S3d modes for their games.

With a famine of programmers working with the API, in that location wasn't enough external investigation and feedback to help improve information technology. And and then at that place was the hardware itself -- texture filtering was uncommonly slow, taking far too many clock cycles to sample and blend a bilinear texel. And so at VGA resolution, the chip would just bog downward under the workload, dragging the frame rate into the dirt.

But despite these failings, ViRGE cards actually sold quite well, cheers to its strong 2nd functioning, decent price, and indifferent competition.

Nvidia's very showtime product, the expensive NV1, was launched a few months before S3'south was targeted at the wrong management that 3D graphics was progressing in, and ATI's 3D Rage series, released in April 1996, wasn't much better than the ViRGE.

Information technology would be unfair to be overly disquisitional of S3 at this stage, though. After all, 3D accelerators for the general consumer were in their infancy and information technology would take a number of years for the field to settle. The ViRGE lineup would see a number of models released over a menstruum of 5 years, with faster versions (such as the ViRGE/DX) offering improvements in every surface area.

In 1998, S3 Inc announced a completely new graphics processor: the Savage3D. This chip had far superior texture filtering than the ViRGE (bilinear was at present unmarried bike), although multitexturing was still required multipass rendering -- that is, if you lot wanted to apply ii textures to the same pixel, the whole scene would effectively demand to exist processed twice.

The blueprint also carried better video capabilities, with a born TV encoder and superior scaling and interpolation for MPEG and DVD. S3 even went as far to create their own texture pinch algorithm, chosen S3TC, which would eventually go integrated into the OpenGL and Direct3D APIs.

On paper, it should take been a huge hitting for them. But it wasn't.

Savage times for S3

The start trouble that customers experienced with the Savage3D was simply finding one on the shelves. It was the first graphics processor to be made on a 250nm node, by the UMC Group. But the manufacturer was as well the commencement to be working at this calibration and, invariably, wafer yields were rather poor.

This deficiency of fully functioning dies meant that relatively few add-in board vendors bought the Savage3D, to the indicate that the likes of Hercules was testing each chip from the purchased trays and hand selecting the viable ones. Long term partner, Diamond Multimedia, eschewed the processor altogether.

The drivers on release were notoriously buggy (pre-release ones, given to reviewers, had no OpenGL support at all) and S3 dropped back up for their ain API. But more importantly, the competition was now in full swing. Where the kickoff ViRGE had the market almost to itself, and the bang-up 2D reputation of old to back it up, the Savage3D faced far meatier opponents.

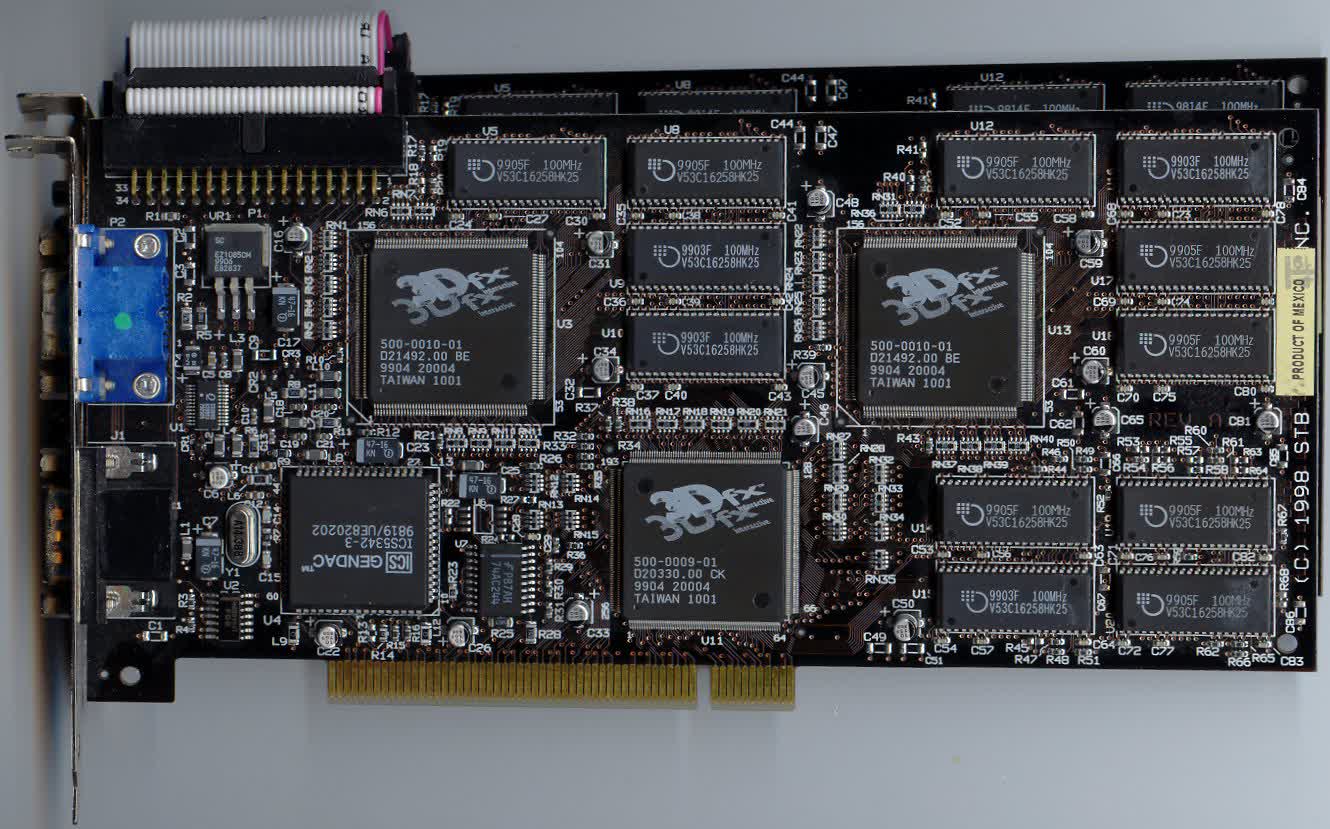

By the fall of 1998, Nvidia had their NV4-powered Riva TNT out, sporting two pixel pipelines, which immune for single pass multitexturing. The same power was likewise fielded by 3Dfx's Voodoo2 cards, but where the Riva TNT's pixel output charge per unit would half with dual textures, the Voodoo2 wasn't affected.

But even in unmarried texturing games, the performance of the Savage3D was disappointing. Vendors couldn't even sell their products at a low price, to undercut the opposition, due to the limited availability of the chips.

S3 resolved many of these issues within the infinite of a year and the following Savage 4 scrap was very much the product the 3 should accept been. But where S3 was getting things right second time round, the likes of 3Dfx, Matrox, and Nvidia were on form right away.

Thus Savage4-powered cards were no ameliorate than models from the previous year and once once again, OpenGL performance was dismal. At least Diamond were back with S3, and plenty of other vendors churned out numerous models.

The only saving grace for the Savage4 was S3TC. The lossy texture compression system was supported by Quake III Arena and Unreal Tournament (the mega-games of the time) and provided a noticeable heave in visual quality, for very little performance affect.

It was within this year that S3 Inc decided to splash its greenbacks effectually, purchasing the avails and IP of beau graphics carte du jour company Number 9 in December (and then licencing information technology back to that company'due south design engineers 2 years later). Then, in the summer of 2000, S3 merged with long-term chum Diamond Multimedia, in a movement to expand their product portfolio.

The newly wedded couple's first offspring was the Savage 2000, S3's first graphics chip to offering Direct3D vii.0 compatibility. The rendering catchphrase of this era was 'Hardware Transform and Lighting' (TnL); instead of the CPU being used to process all of the geometry in a 3D scene, this stage in the chain was washed by the graphics processor.

With ii pixel pipelines, each fielding two texture units, and a clock speed of 125 MHz, the Barbarous 2000 was within spitting altitude of Nvidia's new GeForce 256. Just, to perhaps fiddling surprise, that wasn't the case -- yet once again, drivers permit the product downwards. On release, the hardware TnL wasn't supported, and when it did finally announced, the results were ofttimes buggy and slow.

Overall, it wasn't actually a bad graphics card, information technology merely wasn't as good as the competition (the poor Direct3D performance didn't matters either) nor significantly cheaper. For all S3's long history of blueprint excellence and marketplace leadership, they were now floundering, seemingly lost at sea.

All change at the captain

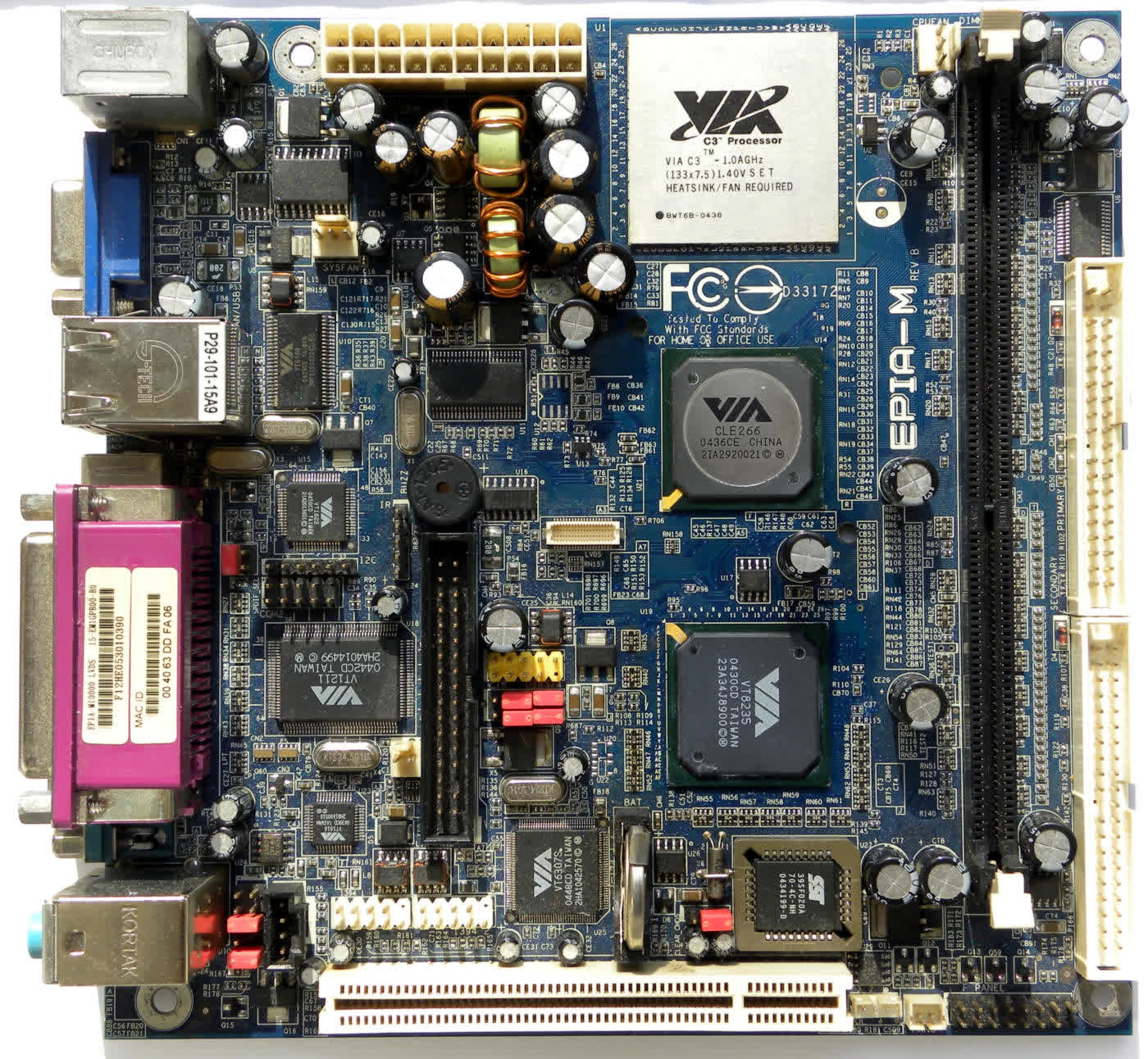

Just 3 months after S3 Inc and Diamond Multimedia appear their merger, the company rebranded itself as SONICblue and in 2001, sold the graphics division to Taiwanese manufacturer, VIA Technologies.

SONICblue would focus on the multimedia industry, making consumer electronic products such every bit video recorders and MP3 players, before shutting downwards and filing for bankruptcy in 2003. S3, though, would live on with an entirely unoriginal new name (S3 Graphics) and a new purpose: integrated chipsets.

At the start of the millennium, CPUs from AMD and Intel -- such equally the Athlon XP and Pentium Iii -- didn't have a graphics processor built into them. To go a video output from your PC, you lot needed an add together-in graphics carte du jour or, equally was the trend then, a motherboard that a chipset with graphics capability.

VIA Technologies was very competitive in the motherboard sector for a while, and then the purchase of S3 fabricated a lot of sense. Rather than creating something new from scratch, the engineers took elements from previous graphics cards: the 2D and media engines from the Brutal 2000 and the 3D pipelines from the Savage4 were melded together to brand the ProSavage organisation.

Part of the reason every bit to why S3's before products could exist sold cheaper than Nvidia'south, for example, was the fact that their designs were much smaller. The processors used fewer transistors and the resulting die expanse was much smaller, making them ideal for chipset integration.

But with the detached graphics card market now booming, VIA fancied a slice of it for themselves, and so once again into the fray, S3 Graphics returned with the Chrome series of processors in 2004. The beginning model was called the DeltaChrome, featuring full Direct3D nine.0 support, with 4 pipelines for vertex shaders and 8 for pixel shaders.

Past now, ATi and Nvidia were fielding incredibly powerful graphics cards, and both companies were experimenting with additional features beyond those required for D3D ix.0 (such every bit higher order surfaces and provisional flow control). S3 Graphics wisely chose to keep things somewhat simpler and early signs of its performance were encouraging but somewhat mixed.

However, later testing showed the processor (and by now, we were calling them GPUs) to have serious issues when using anti-aliasing. But VIA and S3 Graphics persevered, and the Chrome line upwards continued for five more than years, switching to a unified shader architecture in 2008.

These later models were very much at the bottom end of gaming performance, being no amend (and typically worse) than the budget sector offerings from ATi and Nvidia. Their simply saving grace was the toll: the Chrome 530 GT, for example, had an MSRP of only $55.

These would exist the terminal discrete graphics cards designed past S3 Graphics, although VIA Technologies continued to use their GPUs as integrated components in their motherboard chipsets. Simply in 2022, VIA called information technology quits and sold off the entirety of S3 Graphics to another Taiwanese electronics giant called HTC.

Why this phone manufacturer would buy a GPU vendor may seem to be somewhat of a puzzle. Different Apple, HTC didn't design its ain chips for its phones, instead relying on offerings from Qualcomm, Samsung, and Texas Instruments. The buy was purely to expand their IP portfolio, to generate income from licencing the patents for S3TC.

Only a name and addicted memories are left

There hasn't been a chip or menu sporting the name of S3 or S3 Graphics for over a decade at present, and we are unlikely to ever encounter one, given that HTC has done zero with the IP since purchasing them all those years ago. So we're merely left with the name, memories adept and bad, and perhaps a few questions as to why it all went and so wrong for them.

In the 2D acceleration era of graphics cards, S3 was almost untouchable and held a considerable piece of the market. They conspicuously had expert engineers in this area, but that doesn't automatically translate into beingness masters of the world of polygons. Yep, the ViRGE was underwhelming and the Savage3D was released besides early, with manufacturing problems and poor drivers besmirching S3's reputation.

But these could have been solved in time, every bit the overall designs were fundamentally audio. Instead, the company's management chose a different tack -- buying up another failing graphics company, then merging with a consumer electronics group, before finally throwing in the towel altogether.

Other great names of that fourth dimension (3dfx, Rendition, BitBoys, to name just a few) all followed a similar path and their products were sometimes the best around. And just like S3, they're now simply footnotes in history, absorbed into other companies or lost to Wikipedia pages.

The story of S3 shows that in the earth of semiconductors and PCs, nothing can be taken for granted, and connected success is a complex combination of inspired engineering, difficult piece of work, and a fair degree of luck. Their products are no more than, and the proper noun is gone, but they're certainly non forgotten.

Source: https://www.techspot.com/news/89693-s3-graphics-gone-but-not-forgotten.html

Posted by: baumobee1968.blogspot.com

0 Response to "S3 Graphics: Gone But Not Forgotten"

Post a Comment